The Rose of the Desert, Damascus, Syria, Middle East

Heartfelt Memoirs from Courtyards and Light

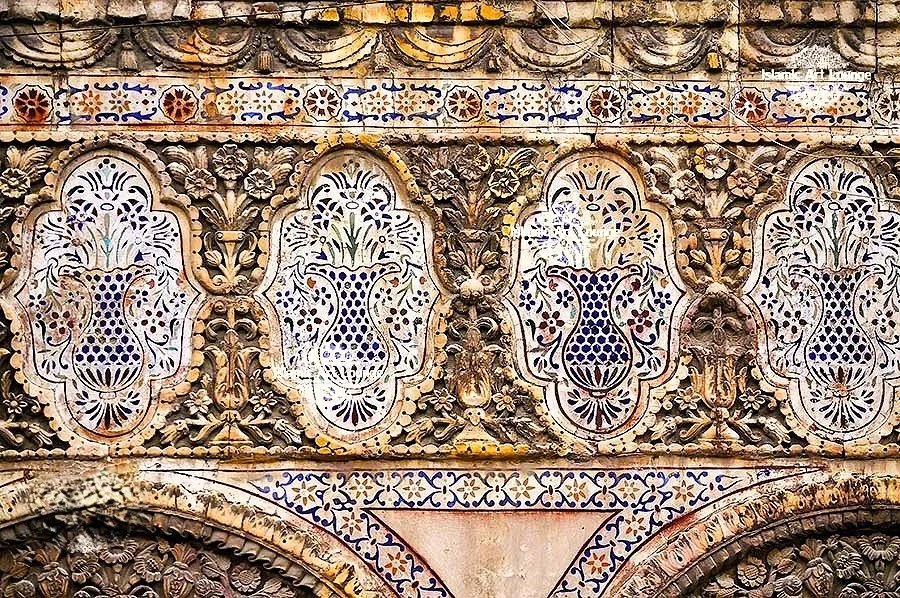

Carved stone in Bait Lisbona, an old courtyard house in Damascus

It was a March afternoon at the dawn of the 1990s when I left the Cham Palace Hotel in Damascus, stepping into the car that would carry me to a dear friend’s mansion. The sun was setting, bathing the congested avenues in a wash of gold as the first streetlights began to flicker. Yet even amidst the bustle, the city’s timeless charm endured—born of the Ghouta oasis, famed for its orchards, pomegranates, and roses, its bustling souks and khans, with the Barada River tumbling down from Mount Hermon in the southern Anti-Lebanon range.

A traveller of the nineteenth century once observed that just as the black veil concealed the beauty of its women, so Damascus jealously guarded its true treasures: the interiors of its houses, which, once entered, transported one directly into the tales of One Thousand and One Nights. It was a city that revealed itself only to those willing to cross its threshold.

Lady Jane Digby el-Mezrab

Among those who fell irrevocably under its spell was Jane Digby, the English aristocrat who arrived in the nineteenth century and never truly left. Casting aside the strictures of Victorian society, she adopted local dress and customs, married a Bedouin sheikh, and made Damascus her home—becoming a living bridge between Europe and the Arab world, a legend among the long procession of travellers who discovered here not merely a destination, but a destiny.

In many ways, Damascus reminded me of Cairo—smaller, perhaps, and less monumental, yet equally rich in artistry. Life here preserved its traditions with quiet devotion: courtyards scented with jasmine and lemon trees, canaries singing in filigreed cages, and the Liwan, where families gathered on warm summer nights.

Liwan-lined courtyard, a haven for refreshing evenings under the open sky - Courtesy: Tim Beddow of the book DAMASCUS Hidden Treasures of the Old City

Encased within medieval walls and crowned by the Umayyad Grand Mosque, the old city appeared like a jewel when viewed from Salihiyah Hill. European travellers glimpsed its white minarets shimmering amidst the green oasis, while the desert stretched endlessly beyond. The Prophet Mohammed, dazzled by its beauty, once passed by without entering, saying that in Paradise one may enter only once. For camel drivers arriving from the depths of the Arabian desert, Damascus was a sanctuary—its murmuring waters, palm trees, orange groves, pomegranates, and succulent peaches offering welcome reprieve. Through earthquakes, fires, floods, and looting, the city endured, its houses rebuilt each time, more beautiful than before.

Even before the French Mandate, noble families began moving from the old city to modern villas beyond the walls. Nadia’s family home stood in Salihiyah, then a suburb of Damascus, after her grandfather returned from Paris and left behind the family Bait – the old courtyard house – near the goldsmiths’ souk. The family had prospered for centuries, trading thoroughbred horses, holding a near-monopoly across the Middle East.

Maktab Anbar Mansion: exquisite decorative detail

Nadia, my dear friend, though she had left Damascus only to study in Paris, carried the city in her heart. She longed for its old streets lined with Peugeots, Citroëns, and Chevrolets; for its familiar sounds, the solemn call of the muezzin. Even from afar, she would murmur with tender nostalgia: “In the basin under the fountain of our courtyard, the moon is still reflected.”

Embark on a journey with my Books in English